Living with leukaemia

This year — 2020 — became my 35th on this round old rock.

Of those 35 years, I’ve now been living with a chronic, terminal cancer for more years than I've not.

In summer of 2001 I was diagnosed with Chronic Myelogenous Leukaemia. I was 17 years old.

As those who know me can attest; my memory isn't the sharpest.

I remember that day clearly.

My dad had driven to collect me from my girlfriend's house, and I was feeling particularly weak. The truth is I'd been feeling weak for months. My legs and hips had in recent weeks turned almost entirely purple with bruising that looked like I'd fallen from a mountain.

When the weakness started, what was probably a good few months prior, I attributed it to my lifestyle. Getting up early for college (having to be on a bus at 7am), not going to bed early enough, probably not eating all that well. Burning the candle at both ends.

I was on the loo one day when I noticed the bruising. I looked down and saw my hip and thigh had some nasty purple marking. I was very confused - I couldn't recall taking a tumble. I put it down to a possible knock on a night out after college. It was when the bruising appeared on the other side of my body my concern grew. How could I have fallen, or been knocked on both sides? My mind moved towards thinking something wasn't right. Eventually I plucked up the courage to do what you're never supposed to do - Google your symptoms.

The (Google) results that came back weren't great. Some of it pointed to the possibility of leukaemia and other blood cancers. Concerning. Surely I can't have this? No. The likelihood is miniscule. There has to be some other explanation. A few weeks passed, as I waited for the bruises to subside. They didn't. If anything they were getting worse. The strangest part of the bruising was that they didn't hurt. Bruising on this scale had to hurt. I showed my parents my findings, but they were the same: That's not likely; it will be something trivial. Try not to worry. In those few weeks I was in limbo. In denial.

I'd been waking up every morning feeling like I needed to go back to bed. Knocked for six. And this particular morning I'd had enough.

When my dad arrived, I was miserable, so I mustered the courage to head to the local hospital to see a doctor on our way home. We waited a while, then was seen. I described my symptoms, showed him my bruising. He immediately recommended doing blood tests. They took the bloods and we were told to come back in an hour or so once they'd been processed. Rather than sitting in the waiting room we drove out to the seafront, sat in the car and watched the sea. I had a can of coke from a cafe. We sat, mostly in silence, interspersed with moments of feeble optimism.

When we arrived back at the hospital, we were quickly ushered into a room. There was an air of concern.

It wasn't good.

The consultant started by explaining blood counts. I knew about different blood cells and broadly what they did, but not what levels they were supposed to be. They gave me a brief run down. Yep, yep, white cells, red cells, platelets.

White cell totals, in the normal range, are supposed to be (roughly) between 5 – 10 (×10^3 parts per micro litre).

Mine were over 200. Logically, I asked why. He was reluctant to give me definitive answer, but said a possible cause could be some blood cancer mutations (such as leukaemia) cause the bone marrow (responsible for creating your blood cells) to flood your system with far too many immature white cells. They couldn't confirm this until more tests were done.

My world, in that moment, collapsed.

The ensuing days were a desperate, grey fog. I was bundled in an ambulance and transferred from Scarborough Hospital to Leeds General Infirmary, where I would stay for four days. I don't remember those days nearly as well.

I lost count of the number of tests. I was kept in my own room, but there were other patients on the ward. I was on the forth floor in the old wing of the LGI - a haunting place at best of times. I remember being stood up against the window, staring out at the city square below. A nurse joked - don't do it, it's not that bad. I laughed. The irony wasn't lost on me.

Eventually the diagnosis came; I had Chronic Myelogenous/Myeloid Leukaemia. In the chronic phase. What followed was a lot of consultation, a lot of questions, a lot of harrowing leaflets. New found terms such as Accelerated Phase. Blast Crisis. It made for grim reading. Trying to take it all in, through the fog.

I was sent home with a sack of large, brightly coloured pills (hydroxyurea).

Blood tests were done at doctors surgeries every few days.

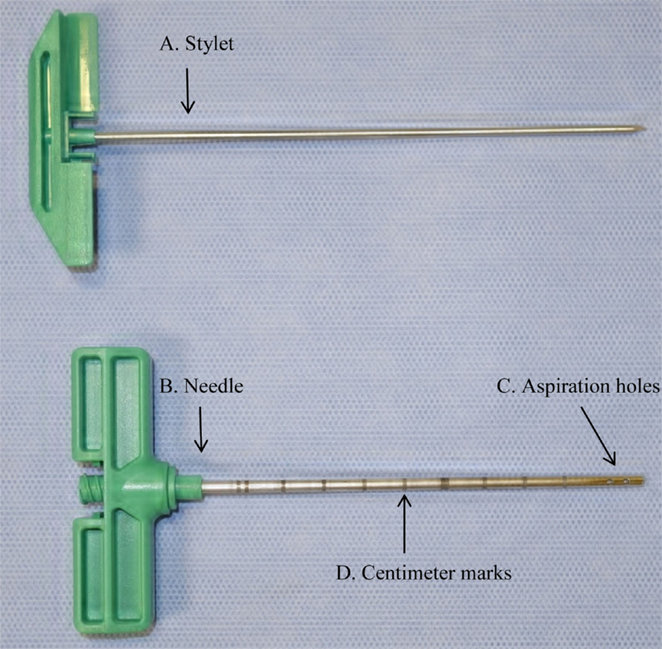

Back to Leeds hospital every two weeks for more bloods, and bone marrow aspiration.

I quickly got used to needles, at least in the arm. One needle however - used in taking a sample of your bone marrow from inside the bone at the back of your hip - is not something you ever get used to. In fact, Bone marrow aspiration is an experience you are unlikely to forget.

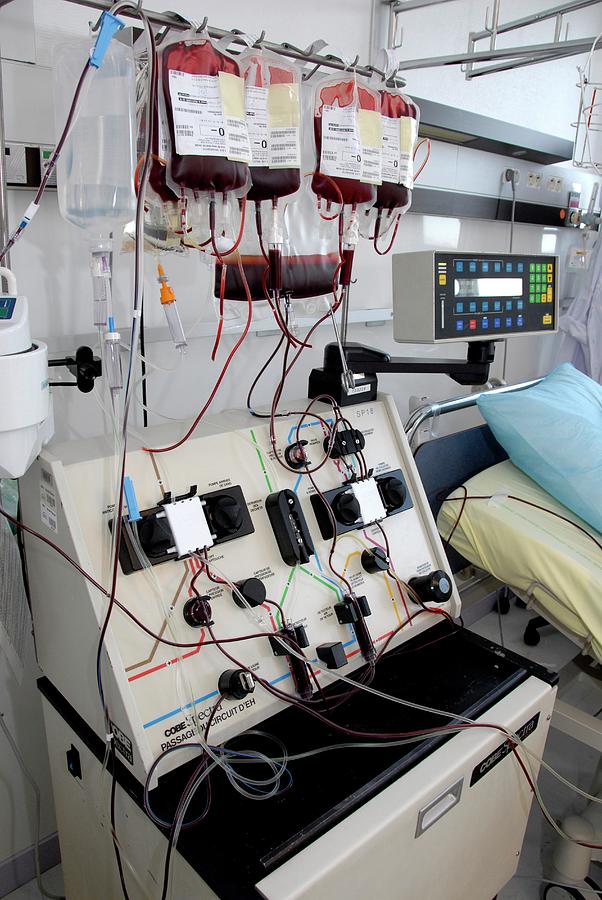

I was booked in and hooked up leukapheresis machine, a machine that pumps blood from one arm, spins it through a series of centrifuges and filters to remove the immature white cells, then the normalised blood is then pumped back into you.

The chemotherapy pills they gave me initially (hydroxyurea) were a blunt instrument, only treating the imbalances in my blood counts. It was made clear that these pills did nothing to combat the cancer itself, and that the 'median survival' (measured in months) wouldn't be changed by taking these.

Thoughts, then, quickly turned to prognosis. Are there any treatments? If so, what? What is the death rate? How long do people live?

The news wasn't great. The 'median survival' (there it is again), from the point of diagnosis, to death, was 4 years.

One of the problems, I was told, is that CML can remain undetected for some time, so it was unclear how long I'd had the disease. Could have been 6 months, could have been 18 months. Doing the quick maths on that one didn't make for happy reading.

I was told there was no specific cause, no hereditary predisposition, merely an extremely unfortunate chromosome mutation. I recall being told at the time that I had more statistical chance of winning the lottery that being diagnosed with CML at 17. I know which I'd have preferred.

CML is more common in males than in females (1.4:1) and appears more commonly in the elderly with a median age at diagnosis of 65 years. Exposure to ionising radiation is a risk factor, based on a 50-fold higher incidence of CML in Hiroshima and Nagasaki nuclear bombing survivors.

I was advised against having children, as it wouldn't be fair on them.

Back in 2001, treatment consisted of two main options, or just leaving it to run its course.

1. A Bone Marrow Transplant

The first successful transplant was performed in New York in the late 1950s. The transplant involved identical twins, one of whom had leukaemia.

There are essentially two types of bone marrow transplant. The first, from a related (sibling) donor. The second, from an unrelated donor that is selected from a bone marrow register. The first is far more preferable as it carries much less risk. There's a rather depressing 25% chance any given sibling is a bone marrow match. Unfortunately my sister wasn't. My samples were punched into the bone marrow register, then I waited. Eventually I had news that they'd found a 'suitable' match. Suitable is key here, as an unrelated transplant is no walk in the park.

A bone marrow transplant is a marathon, not a sprint. The entire process lasts months, followed by intense monitoring.

You start off with a mixture of intensive radiation, coupled with rounds of chemotherapy. The initial aim is to wipe out your broken immune system in its entirety. To nuke every last nook and cranny of your bone marrow within your bones. The first problem here is that if the treatments miss even a small amount, that will proliferate again and you'll be back to square one, after having run the marathon.

The next stage is to have the new immune system grafted back into you with a series of transfusions of stem cells and bone marrow back into your body.

Then you must wait. The problem then shifts. As you're so severely immune-suppressed at this point, any bacteria or virus even looks at you the wrong way and it's game over. It's a real risk that even a mild cold or infection could set in and kill you within hours or days. To try and combat this, you are kept in a special isolation ward, with very few staff and patients. The entire ward is kept held in a positive pressure chamber, where the air pressure inside is much higher than outside, by way of a laminar air flow (LAF) ventilation system. When the air seal is broken (for example when people do enter and exit the ward) air rushes out, rather than in, so airborne contaminants are less likely to flood the chamber. There's also a double-door airlock system on entry to the ward, where those entering have to wear full body scrubs, shoe coverings and decontaminate with sanitiser. If it wasn't for the high risk of dying, it'd be quite cool. Some sci-fi shit right there.

Assuming you keep the nasties at bay, the problem then shifts (again). The next risk is graft-vs-host disease. This delight is where your shiny new immune system happens to decide that the new body it finds itself in a foreign one, and starts attacking it. If this happens, things aren't looking good, and you go downhill fast.

All of this adds up to some unfavourable odds. According to what I was told at the time, around 20% of patients never make it out after hospitalisation. And for the 'lucky' remainder, they're definitively still in the woods.

You are then under close monitoring for a number of years. First for the risk of any graft-vs-host disease. Followed by a waiting game to see whether the clean 'wipe' of the old immune system radiation and chemotherapy did its job, or whether the disease managed to remain, in which case it's only a matter of time before relapse. After 5+ years of monitoring, you're deemed as in remission, where the odds of relapse are more favourable, though there's always a risk. From this stage, should you make it that far, you are finally classified as 'cured'.

2. Interferon Alpha (IFNα)

If patients were too sick or too old to even consider a bone marrow transplant and the toll it takes on the body, or too far along the disease, patients could be given another blunt instrument: interferon-α, which was showing to slow the disease progression, if in the grand scheme of things only a little. It bumped up the median 5-year survival rate to 50–59% compared with 29–44% with just hydroxyurea.

A date set for transplant

My options were thus: brave the ordeal of a bone marrow transplant, with the real risk of not making it out of hospital after the initial suppression, or counting your survival time in months with strong drugs.

You don't have to be as cynical as I am to understand neither were compelling choices. It was bleak, but clinical advice was to go for a transplant. So we started the wheels in motion.

My donor from the register was confirmed. I was given a date on which my transplant was going to start. The table was set.

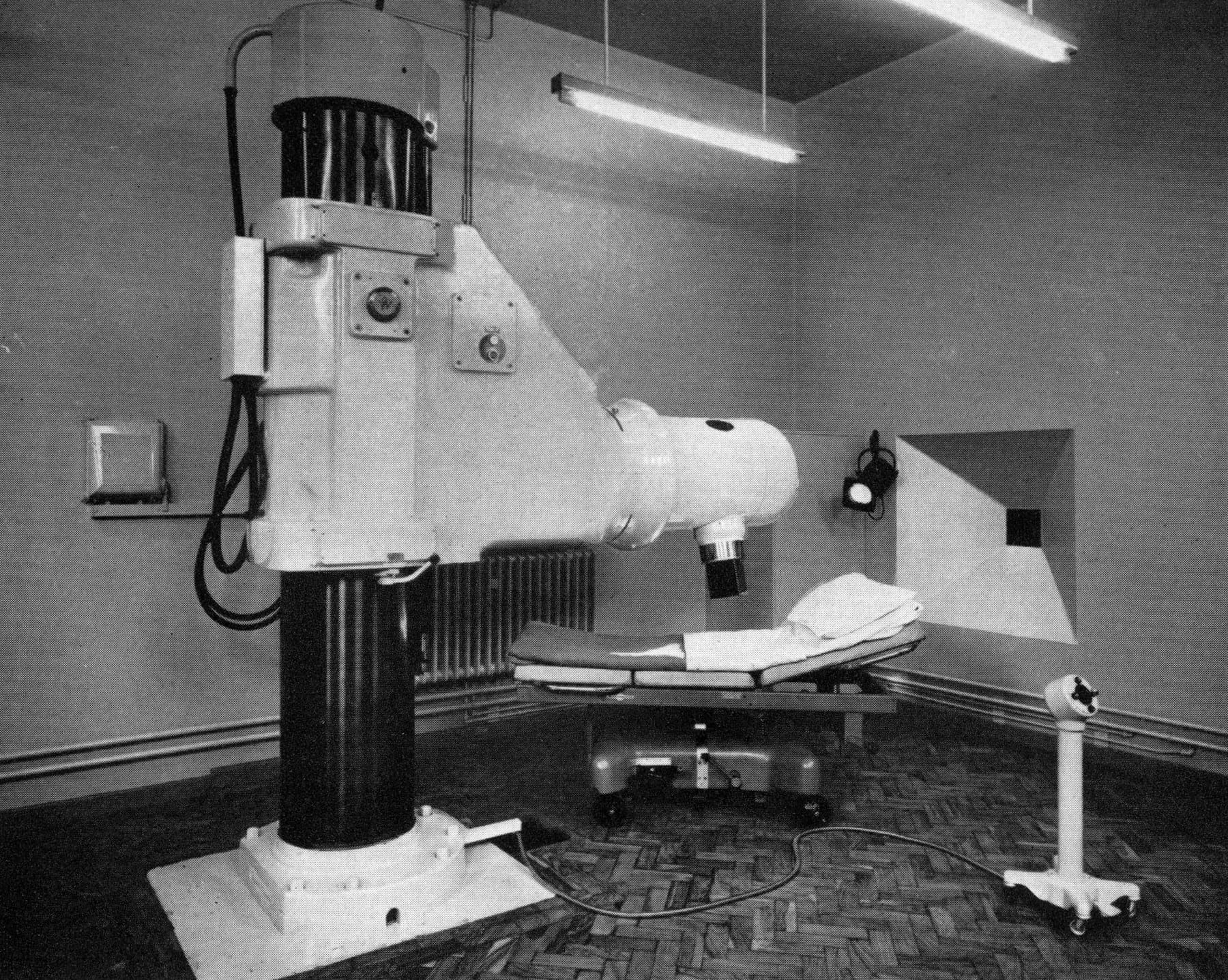

I started with radiotherapy, having sample doses at the radiation facility at the now-closed Cookridge Hospital in Leeds, where a 'High Energy Radiation Centre', providing treatment of cancer with Cobalt-60 and linear accelerator machines since 1950s.

I was strapped and locked on to a table whilst operators switch on the machine, then quickly vacate the room before a red light comes on, and the particle accelerator whirs into life.

I was invited to visit the bone marrow transplant unit, where I would spend the months after my radiation, receiving the high-dose chemotherapy, the bone marrow transplant itself, and the consequent quarantine.

Along came Imatinib

I was back in hospital for a routine blood-work and consultation, not long before my transplant was due. One of the consultant haematologists mentioned some clinical trials of a drug that had been showing promise - Imatinib, a new type of medication called a Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitor (TKI). He explained how they were a brand new type of treatment. And whilst they had shown good results in some people during trials, the historical data on their efficacy just wasn't there. At that time they were not available in the UK, though he seemed confident he would be able to get hold of it soon, as they were in the process of being approved for use by NICE, the governing body that determines which new drugs from trials become available. At that time advice was split, depending on which consultant you spoke to. Some definitely preferred the old tried-and-tested methods of transplant, others were more open to giving the new treatment a chance. Luckily, my consultant at that time sat on a european forum for CML and had heard about the trials over there.

Given the other options available, I was very interested. To me, a promising clinical trail was better placing my faith in than the — frankly miserable — alternatives. I confirmed my intent, and before too much longer was one of the first people in the UK to be prescribed it.

In a dark sense of luck, I'd been diagnosed with cancer at the right time.

As it turns out, the first clinical trial of Imatinib took place in 1998 and the drug received FDA (US) approval in May 2001, becoming available in other parts of the world soon after, moving onto the WHO's list of essential medicines.

I started on the new medication, under careful monitoring. Tests were frequent. I started showing signs that the levels of the disease were coming down.

Fast forward 14 years and the story is much same. Continue taking the medication, dealing with the fluctuations in disease levels, monitoring regularly, deal with the side effects.

There are some who unfortunately cannot take Imatinib (or indeed the newer offshoots Dasatinib, nilotinib, radotinib and bosutinib).

Many experience nausea, vomiting, diarrhoea, headaches, leg aches/cramps, fluid retention, visual disturbances, itchy rashes, lowered resistance to infection, bruising or bleeding, loss of appetite, weight gain, reduced number of blood cells (neutropenia, thrombocytopenia, anemia), and edema.

Severe congestive cardiac failure is an uncommon but recognised side effect of imatinib. Animals treated with large doses of imatinib show toxic damage to the muscle tissue of the heart (myocardium), so much so that human trials almost never took place.

I've certainly experienced many of the more common side effects, but they are a price worth paying for keeping me alive. Again, I deem myself lucky.

The impact of imatinib can't be understated. Due to the development of imatinib and its related treatments, the five year survival rate for people with Chronic Myeloid Leukaemia increased from 31% in 1993, to 59% in 2009, to 70% in 2016.

On the 28th May 2001 it made the cover of Time magazine.

Aside from the physical and mental trauma one would expect, one of the ways in which cancer affected me that I'm most sad about, is that it took from me the optimism of my youth.

At 17, you are at your zenith. The centrepoint of the venn-diagram. On one side: the self-awareness and confidence you gain reaching your late teens - a mind more open to life's possibilities than the innocence of childhood, and the other: a long stretch of time out in front of you, the future life ahead of you, before the rigours of adult life have taken their toll.

At 17, you’re going to live forever. Not a median of 4 more years.

At 17, it's challenging to process feeling lucky if you reach 21.

At 17, you are far enough along your mortal coil to have just started to think about, to dream about, the life ahead of you, with little awareness - let alone anxiety - of your own mortality. That shit normally keeps its head down until much later in one's life. I was fast-tracked from the mind of a 17 year old, to somewhere approaching 70, without the space (of life) between to reflect, without the wisdom to deal with such thoughts, and without the comfort of a 'life-lived'.

It's strange to feel genuinely lucky to be alive. That if modern medicine hadn't intervened, I wouldn't have seen 21.

Cancer, so far, has been relatively kind to me - physically, at least.

Mentally perhaps, it has taken more of a toll.

Why I wrote this

My memory of this section of my life is poor. It takes significant effort to piece together. My mind has been efficient at blotting out a lot of the detail. A coping mechanism, most likely.

I often find myself having to recall this information when I'm speaking to people about my health, whether or not I've known them a significant amount of time. As I've grown older, I felt a need to document these experiences, something I didn't do at the time.